“And yet I think man will never renounce real suffering, that is, destruction and chaos. Why, suffering is the sole origin of consciousness.” - Dostoevsky

“I invent projects of being and of doing in the light of circumstance. This alone I come upon, this alone is given me: circumstance. It is too often forgotten that man is impossible without imagination, without the capacity to invent for himself a conception of life, to “ideate” the character he is going to be. Whether he be original or a plagiarist, man is the novelist of himself.” - Ortega y Gasset

“One may liken dread to dizziness. He whose eye chances to look down into the yawning abyss becomes dizzy. But the reason for it is just as much his eye as it is the precipice. For suppose he had not looked down.

Thus dread is the dizziness of freedom which occurs when the spirit would posit the synthesis, and freedom then gazes down into its own possibility, grasping at finiteness to sustain itself. In this dizziness freedom succumbs.” - Kierkegaard

“What do we mean by saying that existence precedes essence? We mean that man first of all exists, encounters himself, surges up in the world—and defines himself afterwards. If man as the existentialist sees him is not definable, it is because to begin with he is nothing. He will not be anything until later, and then he will be what he makes of himself. Thus, there is no human nature, because there is no God to have a conception of it. Man simply is. Not that he is simply what he conceives himself to be, but he is what he wills, and as he conceives himself after already existing—as he wills to be after that leap towards existence. Man is nothing else but that which he makes of himself. That is the first principle of existentialism.” - Sartre

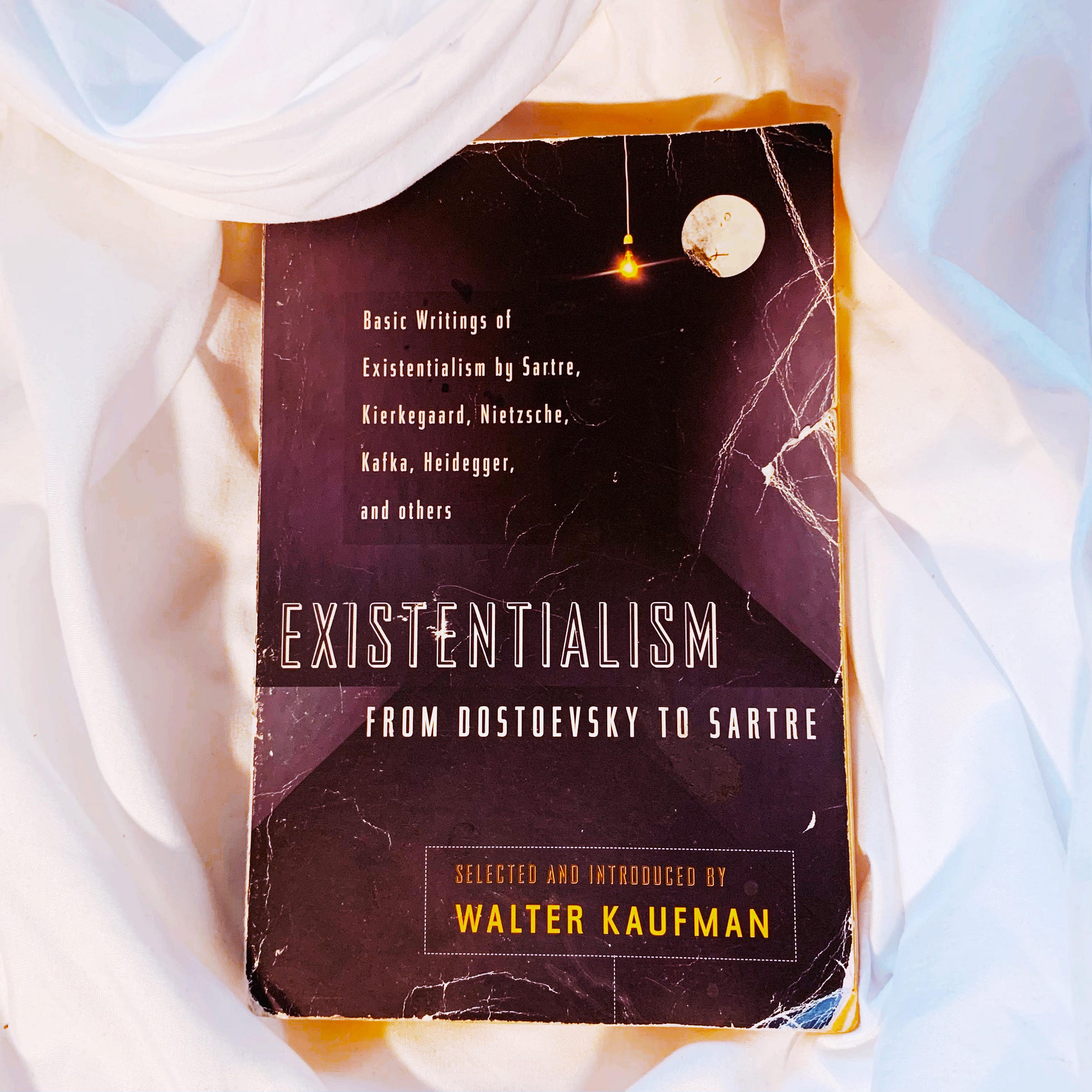

A good anthology is a spectacular treasure. Not only because it is, by its very nature, an economically compact medium from which one can survey, study, and absorb a collected world of information about some phenomenon, but because an anthology, through its galvanizing project, through its particular curation of works, is something more intellectually ravishing than its contents, the curated texts themselves. As Kaufman states in his preface to this anthology of existentialist works: “The present volume is intended to tell a story, and the growing variations of some major themes, the echoes, and the contrasts ought to add not only to the enjoyment but also to the reader’s understanding.”

For a diverse philosophic phenomenon such as existentialism, Kaufman’s Existentialism from Dostoevsky to Sartre is a splendid work from which anyone can begin to sharpen their teeth on the subject of human existence. For the non-philosopher, for the individual unacquainted with existentialism, however, working through this body of texts can be a bit difficult. This is due from the fact that existentialism is not a tidy, neatly-packaged concept to grasp. For one, it has a somewhat ambiguous origin story, and a complicated overwrought history of philosophy to describe. Also, there are multifarious forms and subtopics, ranging over one thinker’s style and technique to the next, making—as Kaufman details—a coherent thread linking each existentialist philosopher’s work to each other often difficult to articulate or, worse, nonexistent. In the end, what does undoubtedly exist between each alleged existentialist philosopher is a radically attentive focus on the conditions, situations, paradoxes, and mysterious possibilities constituting human existence.

For those well-familiar with existentialism, Kaufman’s decision to include the work of a particular individual instead of others, or to include certain works by a thinker instead of another, may be odd or frustrating or delightfully fascinating. The inclusion of Dostoevsky, Nietzsche, or Rilke instead of purely existentialist thinkers like de Beauvoir, Merleau-Ponty, or Franz Fanon, for instance, can come off as a puzzling decision to make. Or better yet, devoting more pages to Jaspers (≈73 pages) instead of giving some extra play time for Ortega y Gasset (a mere four pages), or at least including one illuminating section of Heidegger’s Being and Time, the work that is cited again and again as pretty much being the beginning (not the origin, as Heidegger might explain) and philosophic Rosetta stone of what it fundamentally means to exist.

All in all, though, decent book.

Five stars, for the works.

Four point eight, for the anthology itself.